BY MADS BAJARIAS | Oscar Figuracion Jr. belongs to a dying breed of artists—the Pinoy wildlife illustrator. Natural history is a brave field for a Pinoy artist to be. In the first place, the Philippines has never had a strong tradition of producing wildlife field guides for the layman. Nature appreciation, while becoming popular as a hobby, has yet to gain enough momentum for local publishers to go into the business of producing field guides for the serious Filipino nature enthusiast. Even the most widely-used wildlife field guide in the country, the Philippine bird guide by Robert Kennedy etal. was published by a non-Filipino printing-house, Oxford University Press. The fast-moving technological advancements in digital technology has also dealt a body blow to field expedition illustrators.

Oscar's first brush with natural history happened when he was a college student in 1960s Mindanao. He was working on illustrating a set of native dresses for a university textbook. While he was drawing, someone tapped him on the shoulder and asked if he was interested in joining a wildlife expedition as a field illustrator. That man was Dr. Dioscoro Rabor, the eminent Filipino explorer and wildlife biologist. Oscar immediately said yes.

In Dr. Rabor's expeditions in the 60s and 70s, Oscar's task was to illustrate as accurately and speedily as possible the morphological characteristics of the wildlife specimens that Rabor's expedition members brought from the field. At night, when the expedition hunters came back to camp, Oscar had to draw the prominent features of the animals as part of the documentation process. He had to draw fast and accurate before decay sets in. After drawing the specimens, Oscar handed over the specimens to the taxidermists who were tasked to stuff and preserve in alcohol or cotton the specimens worth preserving.

Today of course, photo-documentation is the norm with digital still cameras and portable video cameras. In the 1980s, Oscar went to the Middle East to work as a cartoonist and only came back in the 1990s when he received some commissions from the various local organizations who were making wildlife field guides. Oscar did a few field guides of birds, fishes and corals. He also illustrated a set of butterflies but was unpublished. When the commissions dried up, he moved to Davao City and is trying to sell wildlife-themed paintings.

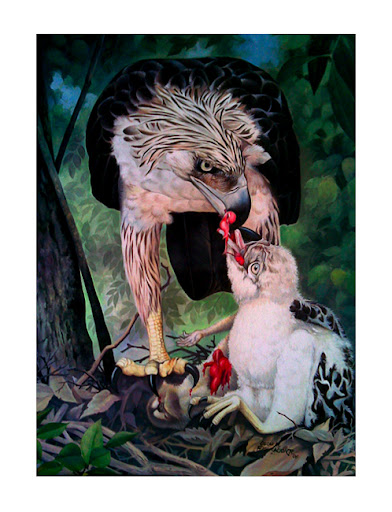

In the painting on top, we see another critically-endangered species, the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), feeding its young. This magnificent bird of prey lays an egg only once every two years in the wild. Tall indigenous hardwoods, their preferred nesting trees, are fast diminishing because of illegal logging and clearcutting of forests to make way for human settlements.

Aside from habitat destruction, hunting is a serious cause of this creature's decline. Even though the law protects it, many fledgelings still get killed by ignorant forest-dwellers who can't recognize a Philippine Eagle when they see one. It must also be noted that the burgeoning Filipino human population means that more and more people from the cities, who have no deep knowledge of the forest, are clearing forestlands where they can make a living. This ignorance means trouble for the native wildlife, and a headache for the real forest-dwellers who are tasked to protect the Eagle.

Many fear that this bird of prey—the country's National Bird—will become extinct within 50 years. If that happens, we have only ourselves to blame.

Poster with an endangered Olive Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) by Oscar Figuracion Jr.

Poster with an endangered Olive Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) by Oscar Figuracion Jr.

Oscar's first brush with natural history happened when he was a college student in 1960s Mindanao. He was working on illustrating a set of native dresses for a university textbook. While he was drawing, someone tapped him on the shoulder and asked if he was interested in joining a wildlife expedition as a field illustrator. That man was Dr. Dioscoro Rabor, the eminent Filipino explorer and wildlife biologist. Oscar immediately said yes.

In Dr. Rabor's expeditions in the 60s and 70s, Oscar's task was to illustrate as accurately and speedily as possible the morphological characteristics of the wildlife specimens that Rabor's expedition members brought from the field. At night, when the expedition hunters came back to camp, Oscar had to draw the prominent features of the animals as part of the documentation process. He had to draw fast and accurate before decay sets in. After drawing the specimens, Oscar handed over the specimens to the taxidermists who were tasked to stuff and preserve in alcohol or cotton the specimens worth preserving.

Today of course, photo-documentation is the norm with digital still cameras and portable video cameras. In the 1980s, Oscar went to the Middle East to work as a cartoonist and only came back in the 1990s when he received some commissions from the various local organizations who were making wildlife field guides. Oscar did a few field guides of birds, fishes and corals. He also illustrated a set of butterflies but was unpublished. When the commissions dried up, he moved to Davao City and is trying to sell wildlife-themed paintings.

In the painting on top, we see another critically-endangered species, the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), feeding its young. This magnificent bird of prey lays an egg only once every two years in the wild. Tall indigenous hardwoods, their preferred nesting trees, are fast diminishing because of illegal logging and clearcutting of forests to make way for human settlements.

Aside from habitat destruction, hunting is a serious cause of this creature's decline. Even though the law protects it, many fledgelings still get killed by ignorant forest-dwellers who can't recognize a Philippine Eagle when they see one. It must also be noted that the burgeoning Filipino human population means that more and more people from the cities, who have no deep knowledge of the forest, are clearing forestlands where they can make a living. This ignorance means trouble for the native wildlife, and a headache for the real forest-dwellers who are tasked to protect the Eagle.

Many fear that this bird of prey—the country's National Bird—will become extinct within 50 years. If that happens, we have only ourselves to blame.

Poster with an endangered Olive Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) by Oscar Figuracion Jr.

Poster with an endangered Olive Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) by Oscar Figuracion Jr.

No comments:

Post a Comment